By Caitlin Hollander

There is a joke that I am almost required to begin this with- and so I will, because I cannot resist a joke, especially not one so well-worn as this:

A Jewish man arrives at Ellis Island. He has been told by his brother, who is already in America, that one should take a new name for their new country. He thinks and thinks, and finally settles on Sam Cohen- it is American, but still Jewish.

Pleased by his choice, he begins his walk up massive flights of stairs carrying his heavy bags. He runs his new name through his head as he walks, committing it to memory. He finally reaches the top of the stairs and is overwhelmed by the hustle and bustle. An immigration officer barks out to him, “NAME?”

The Jew is caught off guard, and flustered, replies “Shoyn fargesin” (“I’ve already forgotten” in Yiddish).

And so the immigration official dutifully writes down his answer, and Sean Ferguson begins his life in America.

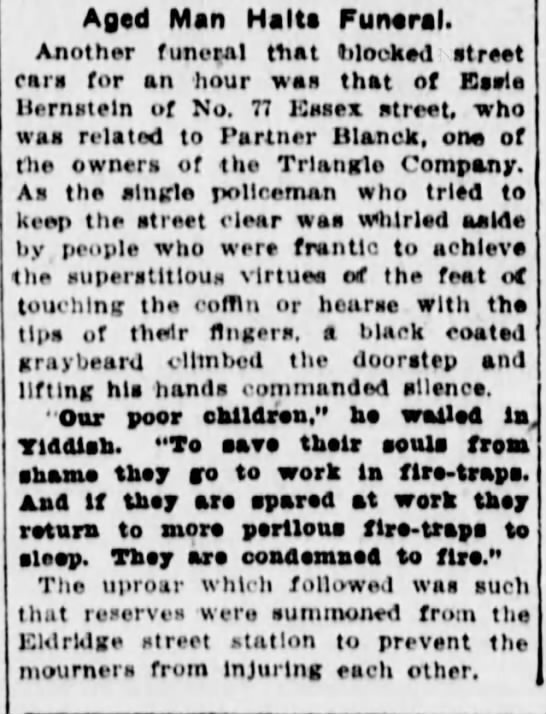

We know this scene very well- it’s ingrained in our culture from movies like The Godfather Part II to jokes like the one I related above. Likewise, we are told by our grandparents “oh, the name was changed at Ellis Island”. And at first glance, it seems to be true- from mobsters (Meyer Lansky was born Meier Suchowlanski) to actors (Jack Benny was Benjamin Kubelsky), everyone seems to have come to America with a different name. This story is an accepted part of the early 20th century immigrant experience- that immigration officials changed the names of immigrants due to racism, misunderstandings, an attempt to “Americanize”, or simply because they did not care.

But none of it is true- simply put, it is one of the greatest urban legends ingrained in the modern American psyche. The commonly given reasons behind these supposed name changes do not hold up to the historical facts of immigration through Ellis Island.

The names recorded at Ellis Island were taken directly from the passenger manifests, which were made up at the port of departure. In addition, Ellis Island employed a number of interpreters who spoke the immigrants’ native languages. In 1911, Commissioner William Williams wrote to Washington, providing both the number of interpreters for each language and asking for funding to hire more.

“Languages known by interpreters: Arabic (2), Albanian (2), Armenian (2), Bohemian Czech (4), Bosnian (1), Bulgarian (5), Croatian (7), Dalmatian (2), Danish (2), Dutch (1), Finnish (1), Flemish (1), French (14), German (14), Greek (8), Herzegovinian (1), Italian (11), Lithuanian (2), Macedonian (1), Hungarian (4), Montenegrin (4), Moravian Czech (1), Norwegian (2), Persian (1), Polish (6), Portuguese (1), Rumanian (4), Russian (6), Ruthenian (4), Serbian (6), Slovak (7), Slovenian (2), Spanish (2), Swedish (3), Turkish (6), and Yiddish (9).”

And in 1914, the chief medical officer, Dr. L.L. Williams wrote to Washington describing his requirements for new interpreters:

“The languages with which they should be familiar are named below in the order of their importance, viz.: Italian, Polish, Yiddish and German, Greek, Russian, Croatian and Slovenian, Lithuanian, Ruthenian and Hungarian. Each of the five interpreters should be able to speak at least two of the languages named and it is very desirable that all of those named should be spoken by the fine interpreters collectively, if practicable.

In addition to these languages, knowledge of Portuguese, Spanish, French, Turkish and Syrian, and Scandinavian languages would increase the usefulness of any of the candidates.”

In short, especially for Jewish immigrants, there was absolutely someone at the port of entry who not only spoke their language but were specifically assigned to interpret for them- often immigrants or children of immigrants themselves. In addition, the manifests were made up at the port of departure, not at the port of entry, and the names were copied down directly from said original manifests- not written down by a clerk at the port of entry.

![From the Inquisition of Lisboa processo for Judaizing of Gaspar Fernandes o Gallego. In Portuguese it states “Disse que elle se chama Gaspar Frz gallego, mercador, e que christão novo de idade de sesenta e dois annos…” which means “[the Defendant"] …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d04c37114376000012d52b9/1575405943747-VE2VJG82XNDO3WKTJ134/PT-TT-TSO-IL-28-12135_m0066.jpg)